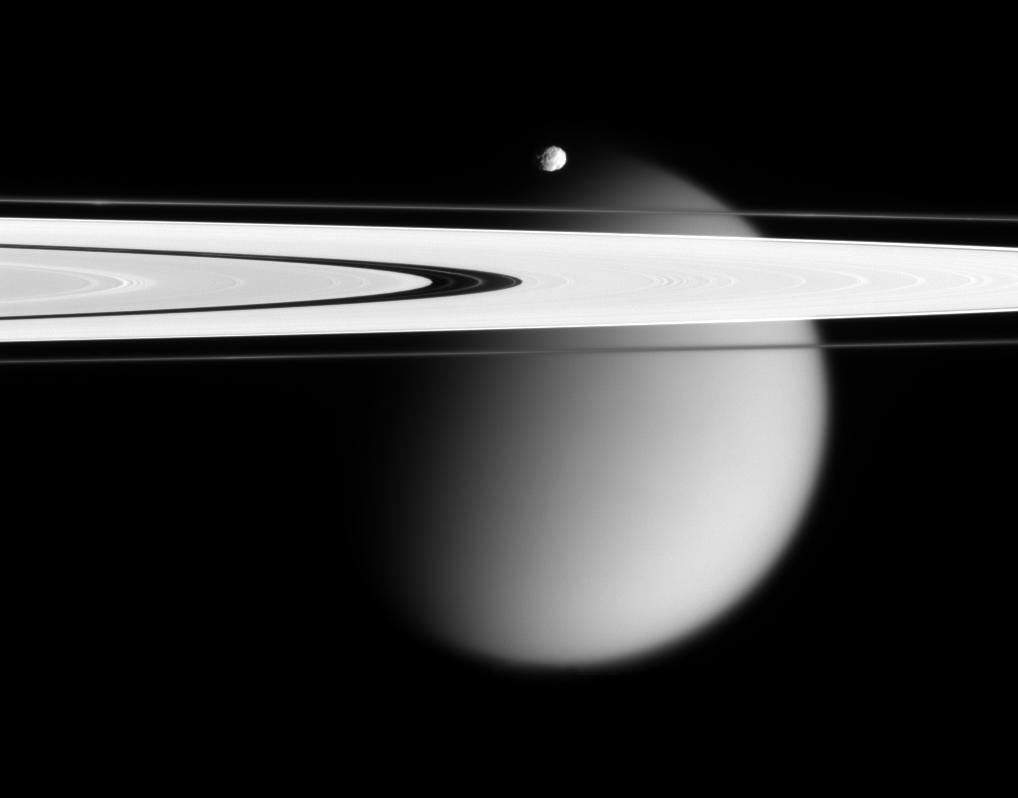

Previously, exogeologists Uisdean Møller and Thorsten Tolba, on a survey of Saturn’s rings, discovered a lifeboat hidden within a sphere of intricately carved ice, at the centre of a labyrinth embedded in the A ring. Now Møller is about to knock on the door and meet the occupant…

The spacesuited figure they had seen from the drone was inside the airlock, still suited up, clearly waiting for him. Møller signalled through the viewport. The stranger waved back and started the opening sequence. Møller felt his heart racing again. The external airlock door opened, a little stiffly, and the figure beckoned him in.

“Steady there,” said Tolba. “Keep your nerve. Remember we know nothing about this dude. Or could be a girl, I guess.”

The external door closed. The airlock was tiny, barely big enough for two men in suits, but before Møller could see the other person’s face, he or she had turned to begin the re-pressurization sequence. When the figure turned back, Møller found it hard to see beyond their visor. The outer shield had been raised, but the strip light down the side of the airlock bounced off the inner visor in harsh stripes. At first, all Møller saw was the eyes, darting and staring. Then he saw that around the eyes there seemed to be a kind of pale fungus, or lichen, some kind of wild organic growth, mould gone mad. He involuntarily retched in horror.

“What the—”

He was glad Tolba was seeing it too. Then he realised it must be hair. Grey-white hair, a beard, floating in the confines of the helmet.

“It’s hair, Thorsten,” he said. “Sweet motherland, I was about ready to piss myself for a minute.”

“Can you talk to him? Suit radio?”

Møller tried to signal to the man, to mime a suit-to-suit connection, but the man shook his head.

“Well, this is going to be an awkward wait,” Møller said drily, half to himself.

The airlock took half an hour to repressurize. Møller used the time to try and gather clues, with Tolba commenting in his ear, but there was frustratingly little to go on. The man’s suit seemed to have once had badges on the sleeve, but these had been cut off. The suit itself, close up, looked like it had come out of a museum. It was like an FSS design, but at least a generation out of date, thought Møller. Or a knock-off produced in the Confederacy. He could see very little of the airlock itself, and had no room to maneuver. It was a relief when the light flashed for the end of the cycle, and the man twisted round to open the inner door.

Inside, the man unclasped the seals on his helmet and took it off slowly. A tangle of greasy grey hair uncoiled and spread out from his head like Medusa’s snakes rendered in smoke. His face was bone-white, and his brown eyes looked huge.

“Now that does not look healthy,” said Tolba. “I’d leave my helmet on if I were you.”

Møller ignored him. He could see a pleading in the stranger’s eyes. He unsealed his own helmet and pulled it over his head, then almost gagged. The air inside the small vessel stank, an odour like the dark places in boggy woods, a foetid mouldy smell. The air scrubbers must have stopped working long ago.

The stranger opened his mouth. It seemed to take a great effort for the words to come out.

“Welcome,” he said.

The stranger began to strip off his spacesuit. Møller said nothing, but decided to leave his on. He held the helmet in one arm, with the camera facing out so that Tolba could follow. He still had the earpiece in. He turned and scanned the space slowly.

The whole ship was a single long compartment, panelled with what looked like storage lockers and some basic instrumentation screens. Tolba was right. It was a lifeboat. Bigger than the Coracle-class lifeboats the SymbioNor exploration vessels were equipped with, but the standard design was recognisable to anyone who had spent time in space.

Part of the cylindrical hull had buckled inward, but otherwise the interior of the lifeboat was remarkably tidy. It all looked clean, with everything stowed in its proper place, despite the smell. But what caught Møller’s attention was the large cross that hung at the far end of the cabin. It seemed to be made of twisted strips of metal, and hung as tall as the diameter of the cabin.

“What in the —” Møller heard Tolba in the background asking their computer for a list of all known missions in which lifeboats had been launched.

The stranger finished de-suiting, stowing his gear safely by the hatch. Møller could now see that although he must once have been a big man, he was shrivelled and emaciated. His breathing sounded laboured. To Møller’s surprise, the man now bowed towards the cross, a kind of microgravity genuflection, before turning back to Møller. Møller decided it was time for him to take the initiative.

“My name is Uisdean Møller of the SymbioNor Corporation, Exogeology Division. I, ah, whom have I the pleasure of addressing?”

The man’s mouth worked again. “My name.” He seemed to dry up, his breath wheezing, then tried again. “Call me Anthony.”

“Anthony?”

“Yes. Pardon me. It’s been a long time since I’ve spoken to another human being.”

“That’s alright,” said Møller. “Take your time.”

“I guess it’s a good job it is you down there and not me,” he heard Tolba say in his ear. “I’d never have your patience for these social niceties.”

“Let me give you a drink,” said Anthony, waving him forward.

Møller sipped cautiously on the pouch of water the man had given him. It tasted fine. Or perhaps he was just getting used to the stench in the cabin. Anthony was floating a few feet away gulping another water pouch. He was staring intently at Møller, exploring him with those huge dark eyes.

“So, Anthony,” said Møller eventually, clearing his throat. “Uh, how long have you been here?”

“Seventeen and a half years,” said Anthony, without having to think about it. There was another silence before Anthony went on. “Do you know, you have been sent here today by God? You are the first person I have set eyes on in these seventeen and a half years and more.”

His speech was becoming more fluent. He spoke Norsk with a discernible Jutland accent.

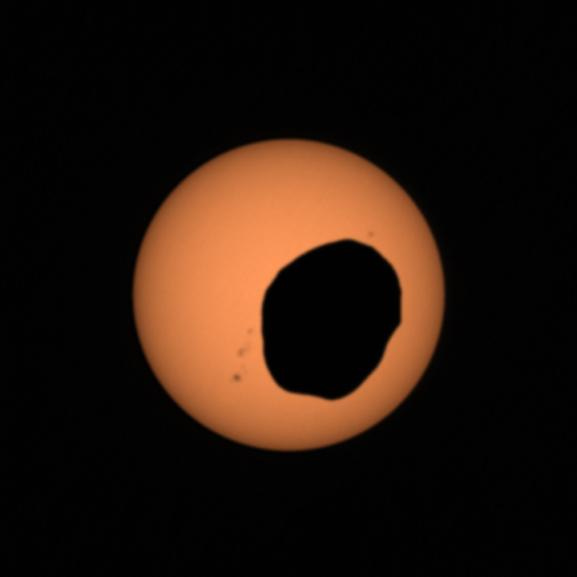

“Seventeen-plus years?” said Tolba. “Uisdean, I’ve got the list of lifeboat launches here. Do you know what happened just under eighteen years ago? The Skíðblaðnir II.”

Møller felt a chill run through him. He had still been a teenager when the FSS colony ship Skíðblaðnir II, bound for Ganymede, had blown up outside Mars orbit with five hundred men, women and children aboard. He had been in school, daydreaming through a lesson on the Poetic Edda, when he heard the news. Was it possible that someone — this wild emaciated man — was a survivor of the worst terrorist attack of the century? Was it possible that anyone could have survived so long?

“This is a lifeboat, isn’t it?” he said, probing. “How did you come to be here?”

“That is what I want to share with you,” said Anthony. He seemed remarkably calm. “I asked the Lord for an opportunity to confess to somebody before I die. And here you are. Would you like something to eat?”

Møller was going to refuse, but it felt rude. Anthony opened one of the lockers and took out two vacuum-sealed emergency nutrition packs. Mashed potato and salmon flavour. Møller ran his finger over the RFSS logo, the space agency of the Federation of Scandinavian States. As a boy, he had longed to join the RFSS.

“I don’t have too many of these left,” said Anthony, “but that doesn’t matter any more. Saved these ones for a special occasion.” He stopped and bowed his head and Møller realised he was praying. Møller’s eyes skittered round the lifeboat, embarrassed, until the old man lifted his head and activated the self-heat strip on his ration pack.

Møller sniffed the mouth of the pack cautiously. It seemed alright, although when he took a bite it had an odd tinny flavour.

“You know, we could transfer over to my ship and get settled over there,” he said. “If you don’t mind my saying, you look like you could do with a good meal. How have you survived this length of time?”

Anthony shook his head. “No, son. I’ll not leave this place. I don’t have much time left. But I want to tell you my story, and you can take that back with you.”

“Go on,” said Møller.

Anthony finished his food before starting his story. He spoke with great solemnity, looking deep into Møller’s eyes.

“I grew up in New Skagen, of Scottish descent on my father’s side. When I was nineteen years old, at university in Gothenburg, I became friends with a classmate who was involved with Saorsa nan Gàidheal. Do you know what I mean by that?”

Møller nodded. Saorsa nan Gàidheal had once been the most active of the political parties seeking an independent Gaelic homeland, although they had been keeping a lower profile in recent years. His uncle had been a member for a while.

“Through him, I became involved myself,” Anthony went on. “I joined a Saorsa cell in Gothenburg. It started off with just small things. Protests, marches, all that. But I wanted more. After my second year, I went over to the Hebrides and was inducted into Claidheamh na Saorsa.” He broke eye contact with Møller.

“What was that?” Møller asked.

Anthony looked up at him again. “Claidheamh was the paramilitary wing of Saorsa. If you don’t know about them, that’s probably a good sign. Lord grant that the sword has become a ploughshare!”

“Wait,” said Møller. “You’ve been out here seventeen, eighteen years? And you’ve had no communication from Earth at all? You know nothing about the world outside?”

“No,” said Anthony. “The lifeboat comms system was crippled from the start. But I will get to that part of the story soon enough.”

“I was young and foolish,” he went on. “That does not excuse the things I did for Claidheamh. My sins are more than the hairs on my head. I was one of the crew that blew up the Bergen-Lerwick cable. I rose in the ranks of the Claidheamh. I changed my name to Maois Caimbeul.”

Møller heard Tolba’s gasp in his ear. His own mind flashed back to the seemingly endless news bulletins reporting on the fate of the Skíðblaðnir II, and the fruitless hunt for Maois Caimbeul, the Solar System’s Most Wanted.

“You’ve heard that name,” said Anthony, with the ghost of a smile. “But I am no longer that man.”

“We have to do something!” he heard Tolba say. But Anthony was already continuing his story.

“One of the things we wanted to undermine,” he said, “was FSS colonialism, expansion into new territory. Our homeland had already been sold out and assimilated. The colony ship seemed like the perfect opportunity to make a statement.”

“But.. five hundred people..” said Møller. He wanted to throw up.

“The plan — my plan — was simply to disable the ship. I never wanted to kill. I was signed on as a junior engineer, and I was just going to damage the engines, force an expensive rescue, and move on to the next target. But it all went wrong.”

Tears formed in Anthony’s eyes then bubbled out in perfect spheroids and drifted out across the cabin, or caught in the grey ropes of floating hair like air bubbles in seaweed.

“I had set the charges based on schematics another member of Claidheamh gave me, then gone to one of the lifeboats to trigger them. The Skíðblaðnir would be stranded. I would have detached from the ship going at its cruise velocity, and get picked up by a hidden Claidheamh yacht a few weeks later. But something went wrong. The whole thing blew. The lifeboat was thrown off course. Steering and comms were wiped out. I was dark and blind. All I got is positioning, so I could see where I was, but I could do nothing about it.

“After six months or so, I realised I was about to hit Saturn. At the speed I was going, I thought that might be the end. But by the grace of God, the angle was just right to get captured and crash into the A-ring here instead, without too much damage.

“I didn’t think I would live very long at first. When I realised what had happened, I decided more than once to just put an end to it. But I never had the nerve. Went to some very dark places in those early months. Years. But God met me in the dark.”

Møller said nothing. Five hundred men, women and children.

“God met me in the dark,” said Anthony again. “I was never a religious man before. But the lifeboat came with some reading material, though it doesn’t have any kind of an AI. So I started reading. Searching. And I found forgiveness, in the end, and peace.”

“Forgiveness?” cried Møller. He shook his head, unable to continue. Anthony looked at him sorrowfully. The tears had kept flowing while he spoke, so his head was now haloed by the droplets, catching the cabin lights like tiny diamonds.

“I know, son,” he said. “I don’t ask you to forgive me. But I found it where it matters. And I changed my name. Anthony, like the desert father. I don’t expect you’ve heard of him. But I thought that if I could use whatever time I had left here to seek and contemplate God, some good could still come from my life.”

Møller was finding it hard to look at Anthony, or Maois Caimbeul, whatever he called himself, or even to breathe the same stinking air with him.

“I have to go,” he muttered. “I have to get back to my ship. And I think you should come with me.”

Anthony shook his head. “I’d never make it to Earth. My body can’t take gravity any more, for one thing. But I doubt I’d even survive the voyage. Cancer, you see.”

Møller looked him in the eyes. Good. He deserves to suffer.

Anthony held his gaze, ignoring the hate in Møller’s eyes. “This thing wasn’t built for this length of exposure,” he went on, his voice steadfast. “Lifeboats, at least in those days, were built for a maximum of twenty people, up to a year at a push. So I was OK for food, more or less. But even if the hull hadn’t taken a beating in the explosion, I would guess that secondary radiation would start to kick in after a year or so. The ice helps. But it was inevitable, eventually. I think it metastatized some time ago.”

“I have to go,” Møller said again, his voice thick.

Anthony nodded resignedly. “I understand. When you report this, tell the families, the bereaved — tell them that I am sorry. I would give my life to get their loved ones back. I have found the forgiveness of the Almighty, but I would like their forgiveness too.”

Møller moved towards the airlock. Before he put his helmet back on, Anthony handed him a small data qube.

“Take this with you,” he said. “This is my confession, my testimony, my apology. And some of my thoughts from over the years. My journal, if you like. Give it to the authorities. I would like my former comrades to see it too, if that’s possible.”

Møller opened one of the suit’s external pockets and tucked the qube inside. His stomach still churned. A tiny droplet of water hit his arm and splintered into a thousand tinier droplets, ricocheting in all directions. He looked up at Anthony and saw the tears still seeding from his eyes like pearls. He was struck suddenly by how, despite the ravages of disease and isolation and the man’s crimes, his eyes burned with life.

“One thing,” said Møller suddenly. He badly wanted answers to so many questions, but this was the first that came to mind. “The ice. Why did you make that strange path outside?”

“Ah, the labyrinth,’ said Anthony. “Well, I had many years with not much to do.” His eyes twinkled briefly. “Have you ever heard of the great cathedral at Chartres? No? This is a way they used to meditate on God. I made this boat my cathedral, with the labyrinth all around it. It’s like life, you see, the way the path turns this way and that, and sometimes you think you’re further than you’ve ever been from the centre, from the truth, but then you turn a corner and there it is. Try it sometime.”

Møller nodded vaguely, then pulled his helmet on with a snap. He didn’t shake Anthony’s hand before entering the airlock.

“We have to take him back,” said Tolba firmly. “I know you’re the ranking officer, Uisdean. But this is a matter of justice and the law of the Federation, not just SymbioNor regulations. And as citizens of the FSS, we have a duty to bring this man to justice.”

Møller nodded wearily. He hadn’t slept. He took a sip of coffee and looked out the viewport at the ring.

“I think he’s kind of already faced justice,” he said. “I don’t know how to explain it.. I was up all night thinking about him. He said he’s not the same man any more.”

Tolba’s eyes turned hard and cold. “My uncle was on the Skíðblaðnir. My mother never recovered.”

Møller held out his hands in a gesture of conciliation. “Don’t worry. I think you’re right, we do need to bring him back. But I can’t manage another EVA today. Think you’re up for it?”

The old man looked like he was asleep. He was strapped into his berth, hair drifting like seaweed, and a quiet smile on his face. When Tolba touched his face, the thermal sensors in his gloves registered cold.

Møller buried him the next day, in a niche in the interior wall of the cathedral-sphere. He’d like that, he thought. And then he followed the labyrinth back to the SymbioNor Xi, to the long voyage back to Ganymede and then back to Earth and back to the shore below his grandmother’s house and the glen with the blue butterflies. And back to Birgitte, if she would have him. If she could forgive him.

Preview image: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Celtic icons created by Freepik - Flaticon

If you enjoyed this story, you might enjoy Phobia, where Mars colonist Asaph Stickney has to deal with an unusual fear...

Phobia

He saw the crescent moon hanging low in the west when he reached the top of the ridge. The sun was still a quarter of the sky’s arc from the horizon, and the moon’s misshapen sickle was pale against the blue. Asaph froze, one foot hovering above the rust-dry dust, stumbled, then threw himself flat to the ground behind…

Great story!

So many thoughts went through my head reading this

But I think the biggest one is I really enjoyed a story that took place in space that didn't have either an American-centric perspective.

I also really love how you brought the character's faith into it - I feel like it's easy to think that people will just become secular as they journey out into the void of space, but I doubt that. I'm no religious scholar, but I think that's a discussion worth having.

There's a lot of really fascinating things to discuss in this piece honestly. I'll be thinking about this for a while!