Phobia

A standalone sci-fi short story, in which Mars colonist Asaph Stickney tries to understand an unaccountable fear.

He saw the crescent moon hanging low in the west when he reached the top of the ridge. The sun was still a quarter of the sky’s arc from the horizon, and the moon’s misshapen sickle was pale against the blue. Asaph froze, one foot hovering above the rust-dry dust, stumbled, then threw himself flat to the ground behind the irrigation embankment. He could hear his own breathing, fast and shallow in his respirator, and the sound of his own heart drumming against his chest. He slithered back down the ridge, the reddish dust scuffing his overalls. He checked the time in his display. Later than he had thought. He hadn’t been careful. Hadn’t moved fast enough.

At the bottom of the hill, gasping for breath, he ran. He tried not to look over his shoulder, but knew that the moon would have cleared the ridge by the time he got back to town. He ran harder, sweat dripping down the inside of his mask. No no no no no no no. Not enough time.

There was no-one else on the road between the farm and the habitat, but when he got closer he saw a couple of guys from the agri team parking their truck by the gate. He recognised Mike Park swinging down from the vehicle’s cab and then turning to stare in his direction before shaking the other guy on the shoulder.

“Asaph, you OK?” Mike’s voice crackled in his earpiece. He couldn’t answer. They started jogging out to meet him. He recognised the other guy now, the botanist dude who’d come out with the last crew, the one Angie thought worked for the FSS. Asaph saw himself reflected in their visors as they grabbed him.

“Panic attack,” Mike was saying to the other guy. Asaph could hear the voice but it seemed disconnected from him, far beyond the wall of his own heartbeat and the breath rasping in and out of his lungs. His respirator was beeping at him, telling him to slow down, but he couldn’t. “It happens from time to time. Let’s get him inside and he’ll be fine.”

They half-carried him through the gate into the habitat and pulled his mask off as soon as the airlock equalised.

“You’re OK, buddy,” said Mike. “You’re OK. Let’s get you home.”

Asaph turned his head to look back out and saw the moon, fatter and more misshapen than before, peeping between the thin trees on the ridge. He screamed.

*****

Angie pushed a steaming mug of tea across the spring-green polymer surface of their tiny kitchen table.

“Asaph, hon,” she said gently, “we need to talk.”

He wrapped his cold hands around the mug. “I guess.”

She gave a small sigh of relief, of gratitude that he was finally willing to admit something was wrong. She unconsciously rubbed her free hand across the swell of her belly. She tried to lock eyes with her husband, but he quickly looked back down at his tea and kept his focus there.

“Ase, what happened up there?”

“I— I dunno. I had a panic attack, I guess.”

“So I gather. Mike and Devine told me that. But I meant up there. Not on the hill just now.” She pointed at the ceiling.

Asaph lifted his head, puzzled.

“Where? On Phobos? Nothing. Nothing happened.”

“Ase, something changed. It’s a month since you were up there and, honey, let’s face it, you’ve been acting pretty odd since then.”

“Have I?”

“I mean, when did you ever have a panic attack before this month? And now that’s the second in a week. And you’ve been hiding indoors, not going out. I’m amazed you even went out to the farm this evening. Thought it was a good thing, thought maybe things were settling down.”

Asaph wrinkled his forehead, trying to piece together what had happened that evening. He felt like an empty beach at low tide. He remembered Angie encouraging him to go for a walk. He remembered thinking he’d give it a try. He remembered seeing the fresh yellow-green buds on the willow trees that grew along the irrigation ditch. And then he remembered running, running and stumbling and running some more, and the solidity of the guys as they took his arms and dragged him into the airlock, and the wetness in his crotch where he had pissed himself.

“I don’t know, Ange,” he said eventually. “I don’t know what the hell is wrong with me. Do you think I should see Dr Andrew?”

She nodded. “I think that would be wise. He might be able to prescribe something, you know?”

“OK.” He took a mouthful of the hot sweet tea. Weariness swelled in him. “OK. I’ll call him tomorrow.”

Angie leaned across the table and kissed him on the forehead. “Good. Now, let’s think about something else, shall we? I know Spring Festival is still a couple of weeks away, but how about we decorate tonight? Make things nice and festive?”

“OK.” Asaph pushed himself up from the table and tried to focus. “Do we need any new ornaments? We have a few spare print credits, I can go over to the print shop if you like?”

Angie stood on her tiptoes and kissed him on the lips this time. “No need. Come on, help me get the box out of the basement.”

*****

“So, doc, am I going spacey?”

Asaph looked away from Dr Andrew Sheldrake as he asked the question, focusing instead on the tangle of lüluo leaves trailing from the doctor’s desk. Every free surface in the doctor’s office seemed filled with the shiny green leaves.

The doctor tapped a finger on his interface then looked at him, eyes gentle, until Asaph lifted his head and looked him in the face.

“I’d say not,” said Dr Sheldrake calmly. “Non-specific space paranoia, by the way, not ‘going spacey’. But your symptoms don’t quite fit with NSP. It’s manifesting more like a kind of agoraphobia, the way you’re describing it. The sudden onset is unusual. But could be some kind of displaced stress, perhaps worry about becoming a father — one of the first children to be born on Mars is a big deal, after all.”

“So what can I do about it?” asked Asaph miserably. “I mean, my job—”

“Hippocrates, what do you think?” asked Dr Sheldrake.

The AI unit, externally nothing more than a simple aluminium cube engraved with the ancient serpent-and-staff motif, blinked and replied in a smooth Midwestern American accent. “I concur. NSP seems unlikely in this case. I recommend further observation to analyse the root cause, perhaps with low-dose Psiloxin.”

Dr Sheldrake nodded. “That’s what I was thinking. Asaph, don’t worry. I’m going to put you on a week’s medical leave. Take some time to relax. Spend some time with Angie. I’d like you to check in with Hippocrates every evening for a quick debrief and report of any symptoms, and I’m also going to prescribe 10 mg Psiloxin, to be taken before you go to bed. Every night for this week. You ever taken Psiloxin? Or anything similar?”

Asaph shook his head. The doctor raised an eyebrow.

“Never? Unusual, in this line of work. Well, you might want to let Angie know you’re on it for this week. There is a — small, I might add — chance of unpredictable side effects. Hippo?”

“For Mr Stickney’s genotype, the probability of undesirable psychological side effects is 0.1%, and the probability of undesirable physical side effects, including headache and nausea, is 0.2%.”

“There you go,” said Dr Sheldrake. “The Psiloxin may help your subconscious untangle some of the neural connections that may be behind your symptoms. At the very least, it should help you relax a little.”

“OK. Thanks, doc.” Asaph stood up slowly.

“Take care, Ase. I’ll meet with you again next week. Hippo here will be in touch when it’s time for your evening chat. Pick up the meds from the dispensary in an hour.”

*****

Asaph glanced anxiously at the dome and the pale sky beyond as he stepped out of the squat building that housed the clinic. No sign of Phobos. He checked his display. Two hours until moonrise. He felt himself relax a fraction. He wondered what to do with himself. Angie would be at the agri lab until late afternoon. He decided to go to Café HG and treat himself to a cappuccino. Maybe Dr Andrew was right and he just needed some downtime. He could come back and pick up the Psiloxin after that. On the way, he called Chief Chang to let her know he wouldn’t be back at Comms Engineering for a few days.

Café HG was one of the quieter social spaces in Weston. There was no-one there when Asaph entered other than a couple of off-duty engineers from Hab Eng chatting in a corner. He nodded at them in a way that showed he didn’t feel like talking, ordered his cappuccino and a donut from the machine, then carried his tray over to a table in the opposite corner, hidden among the greenery. Mostly lüluo again — it grew prolifically and produced a lot of oxygen per leaf — but with some succulents for variety. There was a bookshelf along the back wall near where he sat, with a few pulpbacks, all worth far less than the weight in fuel consumed to get them there, and some ancient board games. Asaph had read all the books before, but picked one at random, his old favourite The Blackwater Saga, to have open in front of him and show that he was occupied.

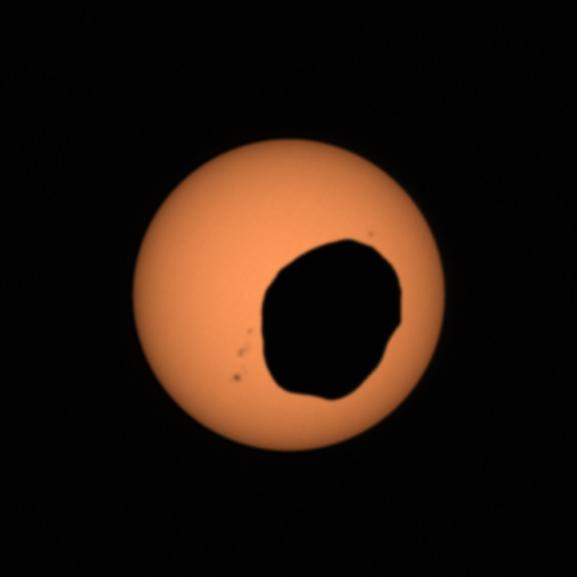

Something was bothering him. He acknowledged that to himself as he took his first sip of coffee and bit into the sugary surface of the donut. Something was bothering him about Phobos. He could think about the moon quite objectively and calmly. But as soon as he saw it above the horizon, he felt such a terror that he was unable to control his actions. Only with Phobos, never with Deimos. And this had started after the maintenance run he had done last month.

He stirred the foam surface of his coffee and looked at the little bubbles of potato milk and thought about the trip. It had been routine. He couldn’t remember anything special happening. Yet, as he stirred, he realised that when he tried to recall the details of the two days he had spent there, it was like opening window curtains only to find yourself staring into a white fog. Like the time his grandad had taken him sailing in Cornwall and they had woken up that morning to find the fog so thick they could see nothing at all beyond the small universe of the boat, apart from shadows and tricks of the eye. He could remember nothing about Phobos, nothing at all.

His forehead wrinkled. He remembered the mission briefing quite clearly. Chief Chang working through the to-do list as usual, her eyes tired as usual. The relay antenna had become slightly misaligned, get up there and reset, may as well take the opportunity to run the five-year service while we’re up there. Could all be done by robot if protocol didn’t require accompanying human presence for all lifeline service jobs. He remembered the launch, and he remembered looking down on the surface of Mars on the way up. He remembered kissing Angie when he got home safely two days later, and he remembered the noodles they’d eaten for dinner that evening. He just couldn’t remember anything that he’d done while actually on the surface of Phobos.

He moved his coffee cup to the side of the table and opened an interface, then brought up the report from the trip. Marconi, the Comms AI, had written it up and he had signed it. Everything normal. The relay antenna had been re-aligned within half an hour of the robot jacking in and running diagnostics. All the other dishes had been checked and cleaned, all functioning within normal parameters. Asaph could see the data, could see his own signature and seal. But if he tried to picture what Phobos had looked like, how it had been to step onto its surface in that low, low gravity, he realised that he was using imagination rather than memory. He closed the interface. The café was warm, but he felt a thin chill knife up his spine.

*****

The hole was like an eye. No, there was more than one. A hundred holes, a hundred eyes. The multiple eyes of a hundred jumping spiders. Asaph screamed and woke up, sitting bolt upright in bed. He was breathing hard. Sweat clammed his crumpled t-shirt to the skin of his back.

Angie was still sleeping peacefully beside him. His mouth was dry. The scream must have been part of his dream. Asaph got up quietly and went to get some water. He wondered if it was a side-effect of the Psiloxin.

*****

He stayed home most of the next day. He read the field report again, in case there was anything he had missed, but again all looked in order. He called Marconi to double-check. Yes, Mr Stickney, everything was completed according to plan. No, Mr Stickney, robot PL-1855 did not report any anomalies. I am happy to run diagnostics on PL-1855 if you wish. Certainly. I will deliver my report within 24 hours. But may I remind you, Mr Stickney, that you are currently on medical leave? Perhaps I should delay the report until you are back in the office?

“No, as soon as you have it,” said Asaph, unable to keep the urgency out of his voice. “I’ll recover faster if I have it.”

*****

“How have you been feeling today, Asaph?”

“OK, thanks, Hippocrates.” Asaph looked wearily at the avatar the medical AI had pushed onto his interface, a rugged-but-handsome Indian man with the look of a genial family doctor.

“How was the Psiloxin last night?”

“OK, I guess. I had a nightmare, is that a side effect?”

“Nightmares may occasionally be an effect of the neural connections established by the drug. On the other hand, it may have been completely unrelated. I am reluctant to draw conclusions at this stage.”

“What about, uh, memory loss?”

“Memory loss is not a known side effect of Psiloxin. What makes you ask about that?”

“I can’t remember what happened when I was on Phobos last month.”

“I see.” The AI avatar templed its virtual fingers together and looked thoughtfully at Asaph. “Traumatic events can cause gaps in memory. However, there is no record of anything unusual from your mission. I see that you have already been checking the reports.”

“Yeah.”

“Let’s continue to monitor, then. I’ll check in with you again tomorrow.”

*****

He looked up and saw the tip of the antenna above him, and Mars huge and rusty above that. The robot was checking the self-cleaning program on one of the other dishes. Asaph had wandered down the crumbling edge beyond the antenna array. He saw his bootprints in the regolith. He saw the hole in the ground ahead of him. And the next one, and the next, each a couple of metres from the last. The holes like eyes.

The hole was perfectly circular, or had been once. The edges were a little frayed. Asaph could fit his entire suited arm into it, up to the elbow. He looked at the hundred holes, the hundred pockmarks on the surface of this irregular crater on this misshapen moon. They reminded him of the woodworm holes they had found in the back of his great-grandmother’s treasured cabinet, in the old house back in Ohio. He felt a great weight of grey sorrow, a scream of pain and despair, seep into him. He woke, weeping and shaking.

******

“Ase, honey, what are you doing?”

Asaph spun round to see Angie coming through the door of their unit. She was looking slowly around the room. Almost every flat surface, horizontal and vertical, was covered in open interfaces. The spring-green table, all the parts of the walls without pictures, the floor where he had pushed back the furniture, the ceiling, even the fleather surface of the narrow sofa. He had even taken down the red paper Spring Festival door decorations to make more space. He had spent all day researching, barely pausing to eat or drink, afraid to close any of the interfaces in case he missed some crucial clue.

“Ange.. this is going to sound crazy, but I think there is something weird going on. With Phobos.”

“OK..” Her voice was gentle, too gentle. “OK, can we clear this up a little and you can tell me about it?”

“No, don’t close that!” he shouted as she stepped towards the table.

“I wasn’t going to,” she replied, a fraction less gently. “But can you at least move it so we can sit down?”

Asaph sheepishly moved the interface over to a wall, shrinking it to fit in the small space between two other windows. “Sorry. That wasn’t such an important one anyway. But Ange, listen. I had this flashback, or something. A couple of flashbacks. I think. So I decided to read up a bit on Phobos, on the geology. But do you know what I found?”

Angie opened the fridge and pulled out a jar of pickled gherkins. She looked tired. “No, I don’t know. Why don’t you go ahead and tell me?”

“I started looking for the reports of the last engineers to go up there before me. Last one was four-plus years ago, before that was more than five years, before that was the construction of the relay station.”

“So what did you find?”

“This is the thing. In the reports, nothing. All normal. But you know what?”

“What?” Angie stabbed a gherkin with a fork. Her eyes were watching him carefully.

“I thought I might look up the guys who made the reports, have a chat. But the last one, the four-plus years ago one, do you remember Rob Thomson?” Asaph spotlighted one of the interfaces on the far wall.

Angie frowned as she looked at the window. “Vaguely. He left not long after we arrived, right?”

“Right. But do you know where he is now? Dead.” Asaph gave an involuntary shiver. “He drank himself to death six months after going back to Earth.” He switched to a different interface. “This is Lamarr Kiesler. Joined the Ganymede expedition three months after her report on Phobos, and now is about as far away from Mars as almost any human has ever been. And this is the relay construction team. Four engineers, worked in shifts of two.” He zoomed in on the photo he was showing. “This guy’s dead, heart failure a month after they completed. This one’s disappeared, off the system, off the grid completely. She’s in rehab, apparently. And this guy is dead, went back to Earth and jumped off a bridge into the Pacific.”

Angie put the jar of pickles on the table. Her eyes were flitting from one interface to another.

“I mean— Angie, what does this mean? What happened to all of them? What happened to me up there?”

He closed the interface on the floor with a swipe of his hand, and began pacing up and down the short length of the unit.

“And you know what?” he went on. “I got the details back from Marconi. The mission robot logs have me out of sight for a good couple of hours on the second day. And my in-suit recorder — guess what — absolute FA for those hours. The camera, the audio, nothing but static. Why wasn’t that in the original mission report?”

A chime sounded. Hippocrates was waiting.

*****

“How are you feeling today, Asaph?”

Asaph hesitated before replying. He didn’t know what was going on. He didn’t know if he could trust the AI.

“OK, thanks.”

“Are you sure? You sound a little agitated, if I may say.”

“Hippocrates, I was out of view of the mission robot for a chunk of time while I was on Phobos, I have no memory of it, and the suit data is screwy. Does that sound like maybe something weird happened while I was up there?”

“Based on all available data about Phobos, as well as your own mission report, that seems unlikely, Asaph. I am discussing the robot logs with Marconi. But, a possibility we must consider, Asaph, is that you have been or are experiencing some psychosis which is interfering with your memory.”

“I’m having flashbacks. They’re not nightmares, they’re flashbacks. Every night. Memories. I’m sure of it.”

“I believe that in your case, Asaph, Psiloxin is not having the effect we hoped. I recommend you not take the dose tonight. I’m making an appointment for you to come in to the clinic tomorrow morning.”

*****

He didn’t see the mouth, at first. Only after he walked past a dozen or so of the holes in the ground did he see it, set into a spur of the cliff below the communications array. There were other footprints in the regolith just outside. Bootprints like his own, and others, long and thin like bird claws.

The mouth had heavy blast doors, forced open long ago. Asaph hesitated on the threshold. It was terribly dark inside, and it felt terribly cold.

He heard their long-dead voices, though he couldn’t see them. They spoke in a language no human could articulate, more like the singing of cicadas than warm wet flesh. Yet he felt their despair, and ancient anguish, and terrible triumph. He saw the covers of the firing tubes click open at the final command, and he saw the torpedoes shoot up, towards the glittering diamond lights of the planet above, the lights of the castles and casinos and cathedrals. He saw the lights extinguished in white fire. And he saw the tubes that had been left unfired. Waiting, until they were needed. Warded with shields and psychoflage more sophisticated than any developed by a human military, designed for a different nervous system, powerful enough to have blinded generations of planetologists and pioneers.

*****

“Angie! Angie, wake up! We have to get out!”

“Asaph, honey, what is it?”

“We have to leave. We have to get off Mars. We have to get back to Earth.”

“Ase, calm down. Are you still taking those meds?”

“The meds have helped me remember, Ange. Phobos could wipe us, all of us, all of Weston, all of every habitat on Mars, off the face of the planet.”

“It’s four in the morning, Ase. We can’t go anywhere at four in the morning. You’ve had a bad dream, baby.”

Angie held onto him in the dark. Neither of them slept. Above the habitat, above the bubble of air and warmth and jokes and ambitions and homesickness and lovemaking and donuts and unfurling leaves and jars of gherkins and red paper New Year decorations, Phobos silently flew.

Brrr.

Nice.

I see what you did there with "Asaph". I thought it was a cool name, too, and used it for a ship.

https://randallhayes.substack.com/p/jamestown-2107-482