The Labyrinth (Part 1)

The first of a two-part science fiction short(ish) story.

“I don’t think I’d ever get tired of this.”

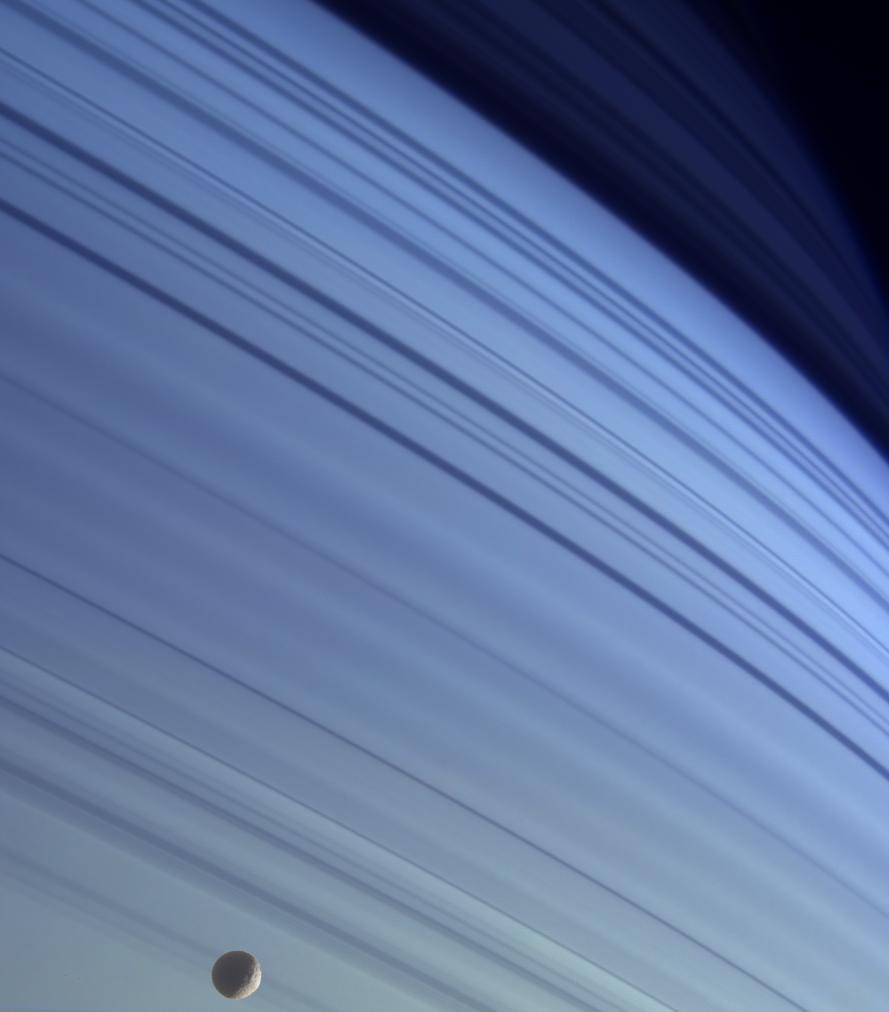

Uisdean Møller was braced side-on to the viewport, allowing him to gaze out without drifting off. Below, the blue curve of Saturn. That dusty summer-dusk blue, fading into the more familiar eggshell-yellow below the equator, had been nagging Møller for weeks, ever since he had seen it with his own eyes. It reminded him of something, but he couldn’t think what. All he got was a flash of memory, of scrambling down the steep sides of the the glen behind the village when he was a boy.

“Yeah.” His partner, Thorsten Tolba, propelled himself out of the galley. “I’ll be glad to get back to some real food though. Just think, cardamom buns… Meanwhile, SymbioNor Special coffee and scrambled eggs is up, get it while it’s hot!”

The thought of cardamom buns made Møller think of Birgitte. Perhaps he should send her a message. But she probably didn’t want to hear from him, he reasoned. He wrapped his guilt away and went back to the viewport to finish his coffee after eating. They only had a few more days orbiting Saturn before the long haul back to Ganymede Station, and Møller knew he would probably never come this way again. He looked out on the portion of troposphere visible from the viewport, the shadows of the rings slicing the powder-blue like the Venetian blinds in an old noir movie. The rings themselves shimmered softly as Svalbard ice in spring twilight, like wet shingle on the beach below his grandmother’s house, like a million uncut diamonds. Møller watched as the terminator approached, finished his coffee, then pushed into the lab.

The SymbioNor Xi was an exogeology research vessel. Møller and Tolba had been sent to follow up the unmanned explorations of Titan before SymbioNor made the final decision about establishing a site there, and studying the rings for a few days at the end of the mission was just the conglomerate’s sop to the academic community. Yet Møller admitted to himself that the rings were the main reason he had applied for the posting. He turned on his music, the classical Celt-rock waves of Runrig’s only surviving album swelling and rippling through his skull, and began to look through the list of regions the computer had suggested for further analysis on their next orbit. The SymbioNor Xi, built to operate with narrow margins and high comms latency, had no capacity for a strong AI. There was only so much space on board for the processors, and the survey ships travelled too far into the solar system to allow for real-time connection with any central server. That was fine by Møller and Tolba. You had to like getting your hands dirty to be a true exogeologist.

“You’re singing again.”

Møller looked up as Tolba entered the lab a couple of hours later. His partner had a dry smile on his face.

“Sorry,” said Møller. He turned his earphones down. After thirteen months together, thirteen months of small irritations and arguments and forgivenesses, he knew it was an argument he wouldn’t win. He stretched, rolling his neck and shoulders. “Fika time?”

“Always time for fika,” replied Tolba, the way he always did. “What have we got today?”

“I believe today is Daim day.” Møller put his hands to the workbench and was about to push himself off towards the galley, when something about the next image in his stack caught his eye.

“Hello, what’s this?”

“What’s what?”

Møller leaned over the screen, then scrolled and zoomed in, then out, then in again. “Interesting.”

“What?” asked Tolba.

“Look. This is a section of the A ring. There’s some odd structure there, do you see it?”

“Hmm.”

They both looked at the image for a few seconds.

“Not the usual propellers or twisties, eh?” said Tolba.

“Nope. A lot smaller than a propeller. Wrong shape.”

The image showed a fuzzy bright circular patch, a blob of higher density in the floes of ice and rubble that made the ring.

“Big chunk of ice?” said Tolba.

“Maybe,” said Møller, checking data. “Temperature, reflectivity fits with ice. Odd shape though. Closer look?”

“Suppose we may as well.”

It was Tolba’s turn to fly the drone. Møller felt a little resentful, given that he had been the one to find the blob, but they had learned that sticking to their turns was overall better for their relationship. At least they could both wear their own headset and see through the drone’s eyes at the same time.

Tolba brought the drone into position above the plane of the ring, matching orbital speed with the boulders and billiards of ice below. The ring was thick at that point, nearly thirty metres. The “surface” of the ring looked normal, but there was something spherical shimmering down below, almost an optical illusion in the kaleidoscope of ring debris.

“There’s a decent gap,” said Møller. “There. Think you can take her in?”

“Yep.” Tolba manoeuvred the drone with delicate twitches of the controls, through what was almost a circular space between medium-sized boulders, then stopped. “What the—”

The drone’s lights were winking off a series of ice chunks, each about the height of a person, stretching out to left and right like a garden wall.

“You ever come across a feature like this?” he asked Møller. Møller shook his head, forgetting that Tolba couldn’t see him with his headset on.

“Go on,” said Møller. “Slowly.”

It looked like the way ahead was blocked by a perpendicular slab of ice, but when the drone crept forward the couple of metres to that point, they found that the path of ice turned sharply to the left and swept in a wide curve further into the ring.

“There is no way this is natural,” said Møller. “No way.” He discovered he was trembling.

“I dunno,” said Tolba. “Plenty of weird geometric features that look manmade. Think of the Giant’s Causeway. Onward?”

They pushed cautiously forward. The path — for they both unconsciously started thinking of it as a path — led them round and back and forward, clockwise and anti-clockwise, all perpendicular to the plane of the ring itself, sometimes seeming to head straight for where the mysterious sphere was hidden, sometimes seeming to sweep away and out towards the edge of the ring. It was immensely disorienting. They could have steered the drone out of the plane of the labyrinthine path, but the space within it was relatively broad and ordered, easier to navigate than the chaotic scattering of ice and rock outside it. By the end, neither of them really believed the path was natural. But nothing could have prepared them for what they saw when the drone finally emerged into view of the sphere.

“No way,” said Tolba, bringing the drone to a halt.

“Impossible,” breathed Møller in the same instant.

The drone’s field of view was largely filled by a sphere of ice. It was the size of a small house, its diameter a little less than the length of the SymbioNor Xi, and it lay maybe five metres from the opening of the path they had followed. It was not perfectly smooth, but was carved in a knotted pattern of loops and intricate whorls, dense in some places and open in others. Light splintered through the ever-shifting drifts of ring ice and scattered on the edges of the carving, while in other places the pattern was stippled by the shadows, making it hard to see the whole. Slowly, Tolba turned the drone in a left-to-right sweep, taking in the view.

“No way,” said Tolba again. “Are we really seeing this? This could be it, this could really be it… Uisdean, we could be the discoverers of the first true alien artifact…”

“Surely not…” said Møller. “No, can’t be.. Look! There!”

“Where?”

“There’s writing. Is that a word? There, a little below centre from where we’re looking.”

Tolba turned the drone a little and moved fractionally closer. Møller was right. Directly opposite the entrance to the path they could now see a circular opening or tunnel, a little larger than human height. It had been hidden in shadow moments earlier but now showed dark like a nostril in the shimmering blue-white of the sphere. Below the opening, they saw what looked like the letters 5HI, carved in almost-Gothic script, each character half the height of a man. The pattern of light and shadow made it difficult to make out.

“Are those letters?” said Tolba doubtfully. “I mean, is that human writing at all?” His fingers twitched the controls, maneuvering the drone to get a better view.

“It reminds me of something,” said Møller, frowning.

“OK, definitely letters.” Tolba sounded disappointed. They were much closer now, and the drone’s headlight played over the sharply-cut lines in the ice. “5HI… some kind of position code? But no-one’s out here, no-one apart from SymbioNor’s even been here for what, fifty years?”

“Wait,” said Møller. “I think we’re looking at it the wrong way round. Turn the drone. Like, rotate it so up is the other way.”

“IHS. That mean anything to you?”

“I dunno. Definitely reminds me of something, but I can’t place it just now.”

“How about we take a look around this thing?”

The drone swung in a slow loop around the sphere, while Møller and Tolba marvelled at the intricacy of the carving. The sphere itself seemed to consist of large chunks of ring ice that had been corralled and anchored together, and sometimes there were rough edges at the joins between one piece and the next that reminded Møller of the old drystone walls at his grandmother’s house. But the outward-facing surfaces of the ice had been somehow shaved smooth, then carved in a complex and infinite knot. Not all the sphere was equally intricate; the carving was richest around the opening below the letters, and seemed less finished, less dense, round the “back.”

“You ever seen the Book of Kells?” said Møller suddenly.

“The what?”

“I took an art history course once, part of my undergrad. I remember these images of Celtic knotwork... or even ancient Norse knotwork, you know? You got it carved in stone sometimes too. But always two-dimensional. This is like, like someone’s made a huge Celtic knot. But three-dimensional. In the A-ring of Saturn.” He shook his head in wonder.

The drone circled back to its starting point. They were about to start another pass around the sphere, at a different angle, when a movement caught their eye. Tolba spun the drone round to face the opening by the letters. In the mouth of the tunnel, where the dazzle of surface ice deepened into blue, the drone’s headlight glinted off something moving. Something alive.

The thing moved closer to the opening. Positioning itself carefully, a figure in a spacesuit raised its right arm in greeting. And then, in the broad careful gestures of international space communication, it beckoned to them.

“One of us needs to go down there,” said Møller.

“Yeah, and it should be me.”

“Uh-uh. I’m sorry, Thorsten, but I’ll pull rank on you if I have to. One of us needs to stay with the ship, one of us needs to investigate, and I have more EVA hours than you. Not to mention that you’re the one with a fiancée waiting for you.”

Tolba scowled at Møller, but said nothing. They had parked the drone in front of the ice sphere, with its programming set to keep it in position relative to the entrance and to notify them if there was any significant movement. The person in the spacesuit had disappeared back inside.

“It’s going to be a hell of an EVA, Uisdean,” said Tolba eventually. “I don’t think we’ve got a tether long enough to get through that maze. You know what company rules are. I mean, I guess we do have to investigate, but…”

“I know. How close to the ring do you think we can get?”

“The ship?” Tolba pursed his lips. “Maybe ten metres?”

“I can run a tether from the ship to the first of these big bits of ice.” Møller pointed to the display. “Then anchor it there. Then attach a second tether at that point. Should be enough to reach as far as the sphere if I go along the edge, parallel to that maze, straight to the centre instead of following all the twists and turns like we did with the drone.”

“I’m pretty sure policy would say the ring environment is unsafe for EVA with our level of kit.”

“I know. But sometimes you need to be a little flexible.”

“Let’s at least see what we can learn from the footage before we jump into this. Try not to go in completely blind.”

Tolba pulled up the video recorded by the drone, and zoomed in on the figure in the spacesuit. The play of light and shadows was tricky. It looked like a standard EVA suit, but it was hard to make out any insignia.

“What do you think? One of ours?” said Møller eventually.

“Maybe? Maybe not? Do you think there’s something about it that looks a bit Confederate?”

Møller chewed on his bottom lip. “Let’s run it through the ship.”

The SymbioNor Xi, as a geological survey vessel, had sophisticated image-processing capabilities despite the limits of its AI. Møller input the drone video into the system and asked it to compare with suit designs in its database.

The output appeared on the display a few minutes later, the words flat and stark.

Match likelihoods as follows:

CSASF 54%±22%

USASA 48%±30%

RFSS 13%±37%

CNSA 5%±2%

All other agencies and corporations negligible. Please note that system information may be incomplete or out of date.“Well, that’s not much good,” said Møller. “Look at the uncertainties on those estimates. All we can say for sure is it’s not China, and we knew that already.”

“Still, better be careful,” said Tolba. “Something American still has the highest probability. And if they’re here…” He shook his head. They both knew it would be an international incident if either the CSA or the USA had infringed on the Federation’s territory.

“What do we get from scanning the thing?” asked Tolba.

Møller was already tapping through the data the drone had sent back.

“Not an awful lot,” he replied. “It’s showing very little useful in the way of EM emissions. What there is has been scattered by the ice. There’s something solid, something metallic, underneath that ice shell, and that’s pretty much all we can say from this.”

A chime rang from the drone monitor. Movement at the ice sphere. They both swung into action, Tolba reaching for the drone controls.

The figure in the spacesuit had re-appeared at the entrance to the sphere. It was holding a large white board of some sort. On the board were scrawled black letters, block capitals, in Norsk: HJELPE. Help.

“Could still be American,” said Tolba as Møller began the process of suiting up. “Could be a secret CSA launch gone wrong. Wouldn’t be the first time.”

“True,” said Møller, adjusting the fit on the inner heat-suit. “But we know one thing: that’s someone in trouble. There’s something seriously wrong if they’re not able to radio us instead of messing around with bits of board and pens. So even if they are the enemy, we have a duty.”

“I know that,” said Tolba shortly. “I’m just saying, be careful, is all.”

“I will.”

By the time he was fully suited, and they had checked and re-checked everything as protocol demanded, and he finally floated in the airlock waiting for the air to cycle, Møller felt his heart racing and his palms sweating inside his gloves. He badly wanted to pee, until he remembered that in his suit he could just do that any time. He did have more EVA hours than Tolba, but it was some time since he had actually done one. SymbioNor protocol for two-person crews was emergencies only.

“All OK,” said Tolba’s voice in his ear. His colleague would watch everything though Møller’s helmet cam. The outer airlock door opened. Møller checked his tether, then pushed himself slowly through the door towards the ring.

Saturn filled his field of view. Møller allowed himself a moment to gaze in wonder. There was the northern winter blue. Common blue butterflies, he thought suddenly. That’s what the colour reminded him of. The powdery wings of the butterflies that flittered in the glen in summer. Then as he rotated himself with a tiny push of his thruster, there was the glittering field of ice, like a fjord in early spring. They were close enough to the ring now that it eclipsed the view of Saturn’s straw-coloured southern hemisphere.

“OK?” asked Tolba.

“Yep. Just admiring the view.” He checked his tether again, fixed his sights on the largest ice chunk near the opening to the labyrinthine path that led to the sphere, and applied a short burst of thrust in that direction. The flight took only a few glorious, exhilarating seconds in which Møller forgot everything except the joy of being alive in the presence of majesty. He came in to the ring slightly too fast, hitting the ice with a jolt that rattled his bones inside his suit.

“Careful!” said Tolba in his ear.

“All good,” he replied. He found a likely-looking crack in the ice, then drilled a piton into it using the suit’s multi-tool. He tested the hold, clipped the tether onto the piton, then connected the end of the second tether he had brought. He took a deep breath.

“All set,” he said. “I’m going in.”

Møller felt very small and naked as he pushed off the ice where the tether was anchored, steering using tiny bursts of thrust and sometimes propelling himself one hand at a time over the ice walls that formed the edges of the path. Fashioning the rough boulders of the ring into those walls had been quite a feat, he reflected. He wished he could get far enough above it to see the pattern, but there was too much ice and debris to allow for a good bird’s eye view.

It took only a few minutes to navigate to the centre, though it had taken the drone a good half-an-hour to go by the curving man-made path. The tether ran out less than a metre from where the drone sat watching. Møller anchored the end with another piton, then pushed himself cautiously into the space in which the sphere sat. He rotated ninety degrees so that he matched the orientation of how the person in the spacesuit had been, with the letters IHS now clear above the entrance tunnel.

The sphere was even more impressive from close up. As Møller’s eye roved over the whorls of carved ice, the pattern weaving and repeating in an intricate dance, he thought of the wicker-work of his grandmother’s chair in the summer-house, and of crystal chandeliers, and of snowflakes, and of Möbius loops, and of the silver earrings he had bought Birgitte that day they went to Kirkwall. He could see it wasn’t perfect — there were occasional rough edges or odd marks where perhaps the carving tool had slipped, or where there was a more obvious join between the chunks of ring ice of which it had been made — but Møller thought it was one of the most beautiful things he’d ever seen. To be here, and to see this, these are the moments that makes life worth living, he thought.

“Here goes,” he said out loud, and started towards the entrance.

Up close, the opening in the sphere was simply a sort of crevasse between three or four segments of ice. On the outside, it had been carved into a smooth circle big enough for a person to enter, but after the first metre the walls were simply rough ice, with some flatter planes where it looked liked bigger protrusions had been sliced off. After about three metres, the crevasse opened out, and Møller saw the ship.

They had known there must be a ship or a habitat of some sort, but Møller was surprised by how small it was. The shell of ice had been thicker than he expected, and the ship sat almost as snugly inside it as the stone of a peach. The tunnel in the ice debouched into a gap of just a couple of metres’ length, and that gap continued around all sides of the airlock to a similar distance. Beyond that, the ice had been packed in until it almost touched the sides of the ship. The side Møller saw now was circular, with the airlock plumb in the centre, and he guessed that he was looking at one of the flat ends of a cylinder.

“Holy mother Freya,” he heard Tolba say. “That’s not a ship. It’s a lifeboat.”

Preview image: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Celtic icons created by Freepik - Flaticon

The Labyrinth (Part 2)

Part 1 Previously, exogeologists Uisdean Møller and Thorsten Tolba, on a survey of Saturn’s rings, discovered a lifeboat hidden within a sphere of intricately carved ice, at the centre of a labyrinth embedded in the A ring. Now Møller is about to knock on the door and meet the occupant…

Well I would very much like to know what happens next!

Oh my goodness!! Please publish the next part quickly!!

Your imagery here is incredible, and I can’t wait to see how all of the references to the natural world and the narrator’s memories will play out through the story.