His Majesty's Advocate v. Grant Stewart Hitchcock

A sci-fi short story based on some real-life science.

Author’s note: To learn more about the real-life science this short story is based on, check out the note at the end!

Two squat sausage-slices of glass, hooked legs rearing snakelike from grey striped ground. Half-light, a tangle of shadows and blades, half-crooked lines and hard angles. Fifteen pairs of eyeballs scanned the image on Screen One, struggling to disentangle twilight greys and white-glinting reflections, then the men and women of the jury turned their dutiful attention back to the Advocate Depute. The silvery coils of her wig bounced as she spoke to the witness.

“Mr Spottiswoode, how long have you worked in the antiques business?”

“Fifty-three years this summer,” said the old man in the witness box.

The Advocate Depute flexed her spidery fingers.

“Mr Spottiswoode, do you recognise the item shown in the image on Screen One?”

The old man cleared his throat. “It looks like a pair of spectacles.”

“And are spectacles commonly available in the antiques trade?”

“Common enough. I sell maybe half-a-dozen pairs a month. Props and fancy dress, mostly. Occasionally an elderly customer who hasn’t had regen.”

“So you are well acquainted, Mr Spottiswoode, with the various styles and fashions of spectacles from different periods?”

“I believe so, yes.”

“How would you describe the pair in the image on Screen One?”

The antiques dealer said nothing for a moment, his eyes roving the shadowy picture.

“Thickish lenses, thickish frames, tortoise-shell effect on the legs. Mid-twentieth century style. Could be reproduction. Hard to say in that light.”

“Thank you, Mr Spottiswoode.” The Advocate Depute called for Exhibit 3B. The LawBot brought out a pair of spectacles in a clear tagged evidence bag and presented them to the witness.

“Mr Spottiswoode, in your expert opinion, could the spectacles in the image on Screen One be a match for the pair you are now holding in your hands?”

The antiques dealer turned the pair of glasses over, glancing between them and the image on the screen.

“It’s possible, yes. Same general pattern. The frames are similar colour and thickness. The only difference is that this pair”— he waved the bag with the spectacles in his hand — “are clearly modern reproductions. The glass is clear, you see. The lenses aren’t correcting anything.”

“Thank you, Mr Spottiswoode.”

The Advocate Depute sipped some water and smiled. She could feel the jury resonating like violin strings in her hand. She glanced at the accused. He was sitting in the dock, leaning forward with his legs crossed. He was wearing a soft dark suit today, and his tie was embroidered with lobsters. He had a peculiar smile on his lips, but the Advocate Depute refused to let it perturb her. The LawBot called the next witness.

Detective Inspector Vincent Pitt took his oath with his shoulders back and his head high. His dress suit was tight and crisp, and his moustache was carefully groomed with vanilla-scented wax. The effect was of a pair of sleek black garden slugs leaning in to kiss on his upper lip.

“D.I. Pitt,” the Advocate Depute began, “please describe for the court the image you see presented on Screen One.”

D.I. Pitt cleared his throat. “This is a FormiScan image taken from the accused, Mr Grant Stewart Hitchcock, on 16th August 2070, by the FormiScan lab at Strathclyde Police Headquarters, Glasgow.”

“And who was present at the time of the scan?”

“Myself, as chief investigating officer for the crime. Detective Sergeant Eòin Rankine, assisting. Dr Dominic Holmes, forensics technician. And the accused, Mr Grant Stewart Hitchcock.” The policeman nodded towards the dock. The accused winked at him, his mouth bent in the same odd smile.

“And in producing this FormiScan image — what is colloquially known as a brainprint — what image or item was given Mr Hitchcock as the prompt?”

“A pair of reproduction spectacles, 1950s style.”

The LawBot brought out the same evidence bag the antiques dealer had been shown.

“Is this the pair of spectacles shown to Mr Hitchcock before his FormiScan?”

The policeman turned the bag over. “Yes, it is.”

“And where was this pair of spectacles obtained?”

“They were retrieved from the scene of the crime, near the victim’s body.”

The Advocate Depute pointed to the screen. “And this is the output from Mr Hitchcock’s brain on being shown this item?”

“Yes, it is.”

There was an expectant pause as the Advocate Depute asked for a new image on Screen Two.

“D.I. Pitt, please describe the image on Screen Two for the court.”

“This is a holoscan of the area where the deceased’s body was recovered.” His voice was smooth as a razor.

The Advocate Depute looked at the jury. Their eyes were flittering over the on-screen image, one or two of them taking side glances at the accused. The Advocate Depute saw revulsion in their looks, and pressed her lips together in satisfaction.

“Zoom in to section B12,” she instructed. The image clicked in past the crook-legged body in the summer dress to show a pair of spectacles lying on the muddy grass and leaf litter by the riverbank. The Advocate Depute adjusted the image orientation until the angle and size of the glasses matched those of the brainprint. The shapes of the lenses and the growth of the grass was a little different, but the jury were nodding before the Advocate Depute even spoke.

“D.I. Pitt, do you believe that the accused’s response in the FormiScan places him at the scene of the crime?”

“I do.”

The prosecution switched to a new set of images. A closer view of the deceased at the crime scene, her brown hair crimped in an antique style, the fern-pattern dress loose and damp on her limp body, a twist of beads around her neck. Then a holograph of the deceased the week before she was strangled, flashing a smile at prospective customers from her InTheFlesh boudoir. And then the FormiScan of the accused’s brain pattern when shown the latter: a twilit tangle of coiff and thick glasses, glint of heavy earrings, and hands tight on her slim throat. The jury murmured in disgust. The Advocate Depute finished her questioning of D.I. Pitt and bowed to the judge, cracking the knuckles on her long white fingers.

Murdo Masayoshi, Defence Counsel, habitually had his eyebrows lifted in such a way that his large forehead furrowed like sand at low tide. It gave him an innocent, surprised look that he knew could play to his advantage. He smiled disarmingly as he called his first witness. Professor Henrietta Faulds stepped into the witness box and took her oath with the air of a heron settling on a riverbank.

“Professor Faulds, what is your occupation?”

“Professor of Forensic Science at Strathclyde University.”

“And how long have you been in this position?”

“At Strathclyde, nine years. Before that, I was Professor at the People’s Public Security University in Beijing for eight years.”

“Tell us, Professor Faulds, what is your particular area of expertise?”

“I have spent most of my career on the development and refinement for forensic purposes of the technology now known as FormiScan.”

“You’re one of the brains behind the brainprint, so to speak?”

The professor stiffened as if preparing to pounce.

“I would like to object to the use of the term brainprint.”

The Defence Counsel’s eyebrows lifted higher, his eyes opened wider, the crumples in his forehead thickened.

“Tell us why that is, Professor Faulds.”

“I feel that that term, although widely used colloquially, is scientifically inaccurate and potentially misleading.”

“Oh? Why is that, Professor?”

Henrietta Faulds twitched the end of her long dark pigtail over her shoulder and scalpelled into an explanation. “In simple terms, the FormiScan technique — that is, Forensic Mental Image Scan — uses MRI scanning — which I’m sure the ladies and gentlemen of the jury are familiar with — to observe a subject’s brain patterns. A Mycroft net — that is, an artificial intelligence trained on this kind of data — is then used to interpret the output from the MRI scan and reconstruct the mental image the subject had constructed at the time of the reading. That is, it shows us what the subject was probably seeing in his or her mind at the time of the scan. I object to the term brainprint, because it is not truly analogous to the fingerprint. The output patterns from the FormiScan are not, at least not yet, as unambiguous and individual as fingerprints are. And for the record, even fingerprinting is still not as accurate as popular media would have people believe.”

The Defence Counsel allowed a moment’s silence for the jury to absorb something of what she had said.

“By ‘not as unambiguous’,” he went on, “do you mean that more than one set of brain patterns could potentially produce the same reconstructed image?”

“Essentially, yes. I must stress that although the accuracy of the FormiScan is high — up to 87% with the latest models — there is a small probability that it will misinterpret the subject’s brain patterns, and there is a small probability that different input prompts could produce basically the same output.”

The Defence Council took a quick look at the jury. Some of them were frowning, in concentration or annoyance. A couple of them were staring vacantly across the courtroom. He looked back to his witness.

“How might that affect its use in a forensic investigation?”

“Well, in a typical FormiScan, the subject is shown a prompt — an image or object — of something connected to the crime. This is usually something very specific to the crime or crime scene. A person unconnected to the crime would most likely produce a mental image that was either just the prompt itself, or some other image unrelated to the crime. Whereas a subject who did have some connection to the crime, for example being present at the scene, is more likely to produce a reflex memory of the scene itself.”

“What kind of circumstances, then, could lead to ambiguous output?”

“Outputs where the reconstructed image is not specific enough to clearly link a subject to the crime scene. For example, if the subject were shown a BZ pistol and the output image was of a blownout corpse consistent with that kind of weapon, and the crime was a killing by that kind of weapon, this could mean that the subject saw the deceased from that particular investigation. On the other hand, if the subject were a veteran, the output image could actually be of a comrade they saw killed with a BZ in the war. It is strongly dependent on context and on the personal history of the subject.”

“What if the subject’s response to the prompt were of a scene from a sim, game or movie he or she had seen?”

The forensics specialist pursed her lips in concentration. “I suppose it’s possible. I think it would be fairly unlikely for the FormiScan to get it wrong in that case, because real-life imagery tends to be, well, less cinematic than televisuals. Less highly coloured. It would be hard to get a fully coincident output.”

“But it is possible?”

Henrietta Faulds crossed her arms. “It is hypothetically possible. Possible, not probable.”

“What if the subject had seen the sim, game or movie dozens or even hundreds of times?”

“I suppose it increases the probability of a subject responding with a scene from the material,” she said slowly. “But there would have to be a proper study to confirm.”

“Thank you, Professor Faulds.”

There was a cat’s-paw of movement among the jury as the Defence Counsel called Grant Stewart Hitchcock to the witness box. The victim’s family hissed at him from the public gallery, and the judge looked sharply round the courtroom.

“Mr Hitchcock,” said Murdo Masayoshi after the preliminaries. His eyes seemed even bigger than before. “Could you tell the court, has Grant Stewart Hitchcock always been your name?”

“No.” The accused smiled as he answered.

“What was the name on your birth certificate?”

“Zelenskyy Robert Stewart.”

“When did you change your name, and why?”

The accused’s eyes seemed to twinkle with bonhomie. “Early in my adolescence,” he said, “I fell in love with the classic art of cinema. By that, I mean the true classics, that magic, ah, intercourse of light and celluloid and music. It’s not so much in fashion in these degenerate days, of course, and the really old films have been almost impossible to get hold of since before the war. But my uncle somehow had a stash of ancient discs, and a player, and when he died it all came to me. The masters. Hitchcock, of course. Nolan. Tarkovsky. Francis Ford Coppola. I loved them all.”

“But you had a particular admiration for the twentieth-century American director Alfred Hitchcock, is that right?”

“He was English, actually. But yes. On my eighteenth birthday I changed my name in his honour.”

“What about your first names?”

The accused sniffed. “Zelenskyys are ten a penny in our generation. I wanted something different. Grant is for Cary Grant, one of the stars of Hitchcock’s films. By happy coincidence, I was already a Stewart, and James Stewart was of course another of his stars.”

The judge cleared her throat and raised an eyebrow at the Defence Counsel, as if to query the relevance of the questioning. A hushed focus had fallen on the jury. Murdo Masayoshi ploughed ahead.

“As a devoted Hitchcock fan, Mr Hitchcock, how often have you seen his works?”

“I would estimate that I’ve viewed his entire oeuvre not less than a hundred times. Certain of his greatest works I’ve seen hundreds, perhaps even a thousand times.”

“And would the film Strangers on a Train, from 1951, be one of the ones you’ve watched more or less?”

“Oh, I estimate I’ve seen that film, oh, five or six hundred times in my lifetime.”

“And prior to 16th August 2070, when you were the subject of the FormiScan, when was the last time you’d watched it?”

“I watched it last on the evening of 15th August.”

“The evening before your FormiScan.”

“Quite so.”

The Defence Counsel turned to the LawBot.

“Could we have Exhibit 27 on Screen Three, please?”

A video clip appeared on the screen. The Defence Counsel clicked play. The jurors leaned forward, their faces showing the effort of interpreting the black-and-white picture as it moved in its two dimensions. They watched the heavy spectacles fall from the woman’s face as the man’s hands tightened around her neck. As the shot cut in to the glasses lying legs-up on the coarse grass, the Defence Counsel paused the video, then inched it forward to line up with the output from the FormiScan.

“This is a scene from the movie Strangers on a Train,” said the Defence Counsel.

A low buzz arose from the public gallery. The judge tapped her gavel and called for order. Murdo Masayoshi’s smile grew broader and his eyebrows higher as the proceedings went on. Professor Faulds was brought back in to testify that the FormiScan image could just as well be the accused’s memory of the film as of the murder victim.

“There is no evidence to place my client at the scene of the crime,” said the Defence Counsel when the Advocate Depute queried the coincidence of the victim’s dress and reproduction spectacles. The Advocate Depute was taut with anger. The Defence Counsel held his hands wide and open. “Burden of proof is on the prosecution,” he said. Grant Stewart Hitchcock smiled and adjusted the knot on his lobster-pattern tie.

The judge charged the jury with their duty and reminded them of their options. The fifteen men and women of Glasgow walked out solemnly behind the LawBot. Three hours later they walked solemnly back in. In the interim, the public gallery had filled with bodies and avatars.

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, have you come to a verdict?”

“We have,” said the spokesman, a rubicund Finnieston fishmonger.

“What is your verdict?”

The spokesman cleared his throat. “Not proven.”

A sussurrus of gasps rose from the public gallery. The victim’s mother sagged in her seat.

“Was this verdict unanimous or by majority?”

“Majority.”

Outside the court, the high-pitched hum of journodrones filled the air and avatars flashed onto the pavement to interview the family as they came out. In the dock, Grant Stewart Hitchcock brushed a speck of dust from his sleeve and stood to shake hands with the Defence Counsel.

Three months later

Grant Stewart Hitchcock looked round the bedroom with a critical eye. He turned down the edge of the antique bedspread and adjusted the hang of the bird prints on the wall, then went into the bathroom and checked the hang of the shower curtain. He looked at his watch. Satisfied, he went into the projection chamber in the adjoining room and riffled through the box of DVDs. There was just about time to watch Psycho once more before she arrived.

This short story was inspired by the real-life science and technology of mental image reconstruction, which

explains in the fascinating and somewhat scary article linked below. I’ve obviously extrapolated far beyond what the technology is currently capable of, but it’s the kind of concept whose implications I think are worth exploring before it ever comes close to reality.Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this story, let me know with a like, comment or share!

If you liked this story, you might also enjoy:

The Best of All Possible Worlds

It’s well and truly winter in my part of the world now, so here’s a chilly short story set in Edinburgh. Enjoy!

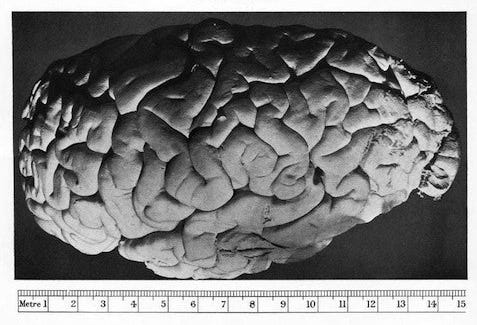

Cover image: "Description of the Brain of Mr. Charles Babbage, F.R.S", by V. Horsley in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character (1896-1934); 1909; Royal Society of London. Page 24, left hemisphere. Public domain, available at https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/a-description-of-the-brain-of-mr-charles-babbage-1909/

Glasses icon: https://myfreedrawings.com/89-eyeglasses-png-and-vector-collection/unisex-glasses-png-63/

Wonderful! This is magnificent work.

Well done!